Throughout history, from the shadow of the Cold War to the digital uncertainty of Y2K, society’s response to imminent crises has been a mirror reflecting our deep-seated propensities for fear, prophetic interpretation, and the search for meaning in the face of the unknown.

I want to delve into the intriguing intersection of historical crises and the surge in apocalyptic thinking that often accompanies them. The dawn of the new millennium, marked by the Y2K scare, is a pivotal moment in this narrative. As the world grappled with the fear of technological collapse due to the Year 2000 bug, a pattern that had been repeating throughout American history became vividly apparent. This pattern, a cyclical dance of fear, prophecy, and survival, echoes through past events like the Cold War’s nuclear dread, the despair of the Great Depression, and the 1918 flu pandemic. Each of these historical moments ignited a unique blend of societal panic, prophetic declarations, and a grappling with the concept of an impending apocalypse. As we explore these historical events, we unveil their profound impact on shaping public consciousness, particularly in the context of Biblical end-times prophecy, revealing a consistent undercurrent of apocalyptic anticipation woven through the fabric of American culture.”

Y2K: The Last Big Problem Before The World Changed.

The year 2000 bug that affected computer systems worldwide had several stages before the problems were eventually solved and the year 2000 arrived. The alarm began to sound (from the viewpoint of the public) around the latter half of 1996, up to New Year’s Eve of 1999. Several stages happened within the American public during this event. Those states were:

Awareness of the problem.

An individual began to sound the alarm that we – society at large – had a problem.

Assignments to fix the problem.

Individuals and groups were assigned tasks to fix the Y2K problem within the public and private sectors.

Minor occurrences of the Y2K predictions came true.

Several small but public instances of Y2K predictions were reported through the media.

The rise of fear.

After people became aware of the general problem and viewed/read about computer failures occurring because of the Y2K issue, fear began to grow within the population.

The rise of the scoffers.

The rise of ridicule within different areas of the private sector began to speak out about the overall problem and the individual that raised the alarm.

The division into groups.

Several groups that arose during the Y2K years were:

- “The doomsday preppers” – these were individuals who thought the worst. They believed that society would fall apart. They stockpiled food and supplies, moved off “the grid,” and found remote places to live. Their lifestyle reflected a “return to simple and secure living.” Their ideology at the beginning – a return to community and connection.

- “The rise of the spiritualists” – during this time, spiritual significance rose around the year 2000. People began to look at what was happening around them and assign a spiritual importance to the problem and division of society.

- “The rise of the prophets” – these people began to look toward Scripture as found in the Holy Bible. They looked at what was going on and found Scripture that seemed to speak to their living times. They warned people to “get right with God through Jesus.” Some of these people splintered off into the doomsday prepper crowd and stockpiled supplies. Their motives were based on prophecies found in the Holy Bible.

- “Normal folks” – these people took some precautions but weren’t totally ruled by fear. They may have avoided certain things, bought a gun, stocked up on some supplies, but kept to their lives before they knew anything about Y2K. Most of them grew fatigued at the constant barrage of news stories about the potential problem and “tuned out.”

The countdown to Y2K.

As the time approached, each group (listed above) did what they thought was needed to “survive” the potential crisis.

The year 2000 arrives – the problem is here.

All the world – specifically America – waits as the clock counts down to the time everyone dreads – the arrival of the new millennium. When 2000 arrived, the world went on as usual.

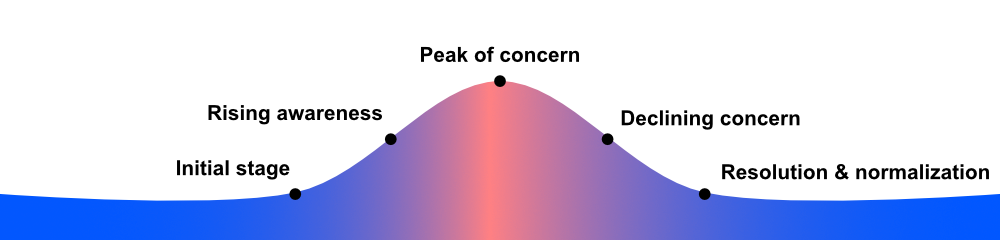

The “Crisis Response Bell Curve”

In the context of our exploration from Y2K to past historical crises, the “Crisis Response Bell Curve” serves as a pivotal framework to understand how societies react to looming threats. This bell curve traces a path from initial awareness, where a problem like the Y2K bug first enters public consciousness, to a crescendo of concern, mirroring the heightened anxieties and preparations as the millennium approached. This peak of collective apprehension is not unique to Y2K; it parallels the intense fears during the Cold War’s nuclear standoff, the desperate struggles of the Great Depression, and the widespread panic of the 1918 pandemic. Following this apex, the curve descends as the anticipated disaster either materializes and is managed or, as in the case of Y2K, passes with fewer repercussions than feared. This declining phase represents a collective sigh of relief and a gradual return to normalcy, a pattern recurring through these diverse historical episodes. The “Crisis Response Bell Curve” encapsulates this ebb and flow of societal anxiety and response, offering a lens through which we can view the human condition under the shadow of impending crises.

Here’s a breakdown of how this pattern aligns with the characteristics of a bell curve:

- Initial Stage (Low Point on the Bell Curve): This corresponds to the early phase, with limited awareness of the problem. In the case of Y2K, this was the period before the late 1990s when the issue was known mostly in technical circles.

- Rising Awareness (Ascending Slope of the Bell Curve): As awareness of the problem grows, more people start to react. This stage encompasses the growing concerns, the spread of information, and the start of preparations. For Y2K, this was the period leading up to the late 1990s, when the public and the media started to pay attention.

- Peak of Concern (Top of the Bell Curve): This is the point of highest intensity in terms of public concern, preparations, and reactions. For Y2K, this peak occurred close to the turn of the millennium, when fears and preparations were at their highest. This phase includes the rise of doomsday preppers, spiritual interpretations, and widespread public concern.

- Declining Concern (Descending Slope of the Bell Curve): After the peak, as the anticipated event occurs or passes without the feared outcomes, concern and attention begin to wane. In the Y2K scenario, this occurred when the year 2000 arrived without the catastrophic failures that many had feared.

- Resolution and Normalization (Low Point on the Bell Curve): Eventually, the issue recedes from public concern, and society returns to a state of normalcy. For Y2K, this was the period after January 1, 2000, when it became clear that the problem had been largely mitigated or was not as severe as anticipated.

This bell curve pattern is a useful framework for understanding how society collectively responds to perceived large-scale threats, with a gradual build-up of concern leading to a peak, followed by a decline as the anticipated crisis is resolved or fails to materialize as feared.

The bell curve in action – a walk through history.

The Y2K event was unique in its technological nature and global impact, but there have been other instances in American history where a perceived large-scale threat led to widespread public concern, preparations, and a mix of reactions similar to those seen during the Y2K scare. Here are a few notable examples:

- The Cold War and the Fear of Nuclear Attack (Late 1940s to Late 1980s):

- Awareness of the Problem: Post-World War II, the growing tension between the USA and the USSR and the development of nuclear weapons made the public aware of the potential for nuclear war.

- Alarm and Assignments to Fix the Problem: Government initiatives like civil defense programs and public information campaigns were launched to prepare citizens for a possible nuclear attack.

- Occurrences and Rise of Fear: Various international crises, such as the Cuban Missile Crisis, heightened fears of nuclear war.

- Scoffers and Division into Groups: While many people built bomb shelters and stockpiled supplies, others were skeptical about the likelihood of a nuclear war or the effectiveness of civil defense measures.

- Countdown and Aftermath: The end of the Cold War and the dissolution of the USSR in 1991 alleviated the immediate fear of nuclear war.

- The Great Depression and the Stock Market Crash of 1929:

- Awareness of the Problem: The economic boom of the 1920s led to excessive speculation in the stock market.

- Alarm and Assignments to Fix the Problem: The stock market crash in October 1929 raised alarms about the economy’s stability.

- Occurrences and Rise of Fear: The ensuing Great Depression saw widespread unemployment, bank failures, and economic hardship.

- The division into Groups: Responses varied from those who desperately sought work to maintain normalcy to others who gave up hope or sought radical political solutions.

- Aftermath: The Depression continued until World War II, leading to an economic recovery.

- The 1918 Influenza Pandemic:

- Awareness of the Problem: In 1918, a deadly influenza virus spread worldwide.

- Alarm and Assignments to Fix the Problem: Public health campaigns were launched, and some cities imposed quarantine measures.

- Occurrences and Rise of Fear: The high mortality rate and rapid spread of the disease caused widespread fear.

- The division into Groups: Public reactions ranged from strict adherence to health guidelines to skepticism about the severity of the pandemic.

- Aftermath: The pandemic eventually subsided by 1920, but it significantly impacted public health policies and awareness.

These events share common elements with the Y2K scare, including initial awareness of a potential problem, public and private sector responses, varying degrees of public fear and skepticism, and different group behaviors in reaction to the perceived threat. However, each event also had its unique aspects and historical context.

Parallels in various Christian sects.

in each of the historical instances I mentioned earlier, there were individuals or groups who interpreted these events in the context of Biblical prophecy and the idea that “the end is near.” This kind of reaction is not uncommon in times of crisis or significant change, where some people turn to religious or spiritual interpretations to make sense of what’s happening. Here’s how this manifested in each event:

- The Cold War and the Fear of Nuclear Attack:

- During the Cold War, the threat of nuclear annihilation led some religious groups and individuals to view these developments as signs of the end times as described in the Bible, particularly in the Book of Revelation.

- Evangelical Christian preachers and authors often linked the tension between the superpowers and the arms race to Biblical prophecies about the end of the world.

- This period saw a rise in the popularity of Christian eschatology, with interpretations often focusing on the potential for global war as a fulfillment of prophecy.

- The Great Depression and the Stock Market Crash of 1929:

- The economic turmoil and social upheaval of the Great Depression also led some to believe that these were the end times prophesied in the Bible.

- Itinerant preachers and some religious sects interpreted the economic collapse, widespread poverty, and social distress as signs of the impending apocalypse.

- This era also saw the rise of new religious movements and sects that focused on end-times prophecy, some of which gained significant followings.

- The 1918 Influenza Pandemic:

- The 1918 flu pandemic, which caused widespread death and suffering, was also seen by some as a sign of the end times.

- Various religious leaders and groups interpreted the pandemic as a fulfillment of Biblical prophecies about plagues and disasters that would occur before the end of the world.

- This interpretation was part of a broader trend of millenarianism and apocalyptic thinking that has often emerged in human history during periods of crisis or significant change.

In each of these cases, interpreting current events as signs of the end times was not universal among all religious people but was a notable phenomenon among certain groups and individuals. The context of each event—the fear of nuclear war, economic collapse, or a global pandemic—provided fertile ground for apocalyptic and prophetic interpretations, particularly among those predisposed towards literal interpretations of Biblical prophecy.

Bringing it all together – a teaching moment to remember

What we see in the above examples is a compelling tapestry of human reaction to crisis, woven through with threads of prophecy and the anticipation of an end. From the existential dread of nuclear war during the Cold War to the technological fears surrounding the Y2K bug, each era reflects a unique manifestation of apocalyptic thinking. These periods of history, marked by profound societal anxiety, have consistently spurred interpretations of Biblical end-times, showcasing a deep-rooted human tendency to seek meaning in moments of uncertainty. The enduring nature of this phenomenon, transcending different crises across decades, underscores a fundamental aspect of our collective psyche. It is a reminder that at the heart of our responses to global threats lies a complex interplay of fear, faith, and the perennial quest to understand our place in the grand narrative of history.”