In a world where snap judgments and assumptions often cloud clear thinking, understanding how to properly structure speculation becomes crucial. This article explores the ancient wisdom and modern science behind distinguishing careful inference from reckless guesswork — and why mastering this skill can make all the difference.

Speculation is a tricky beast. It can guide you to truth, but just as easily lead you into fantasy. Understanding when and how to speculate is crucial, especially when evaluating human behavior. Like following tracks in a dense forest, the first few clues may be reliable, but the deeper you tread without evidence, the greater the risk of getting lost.

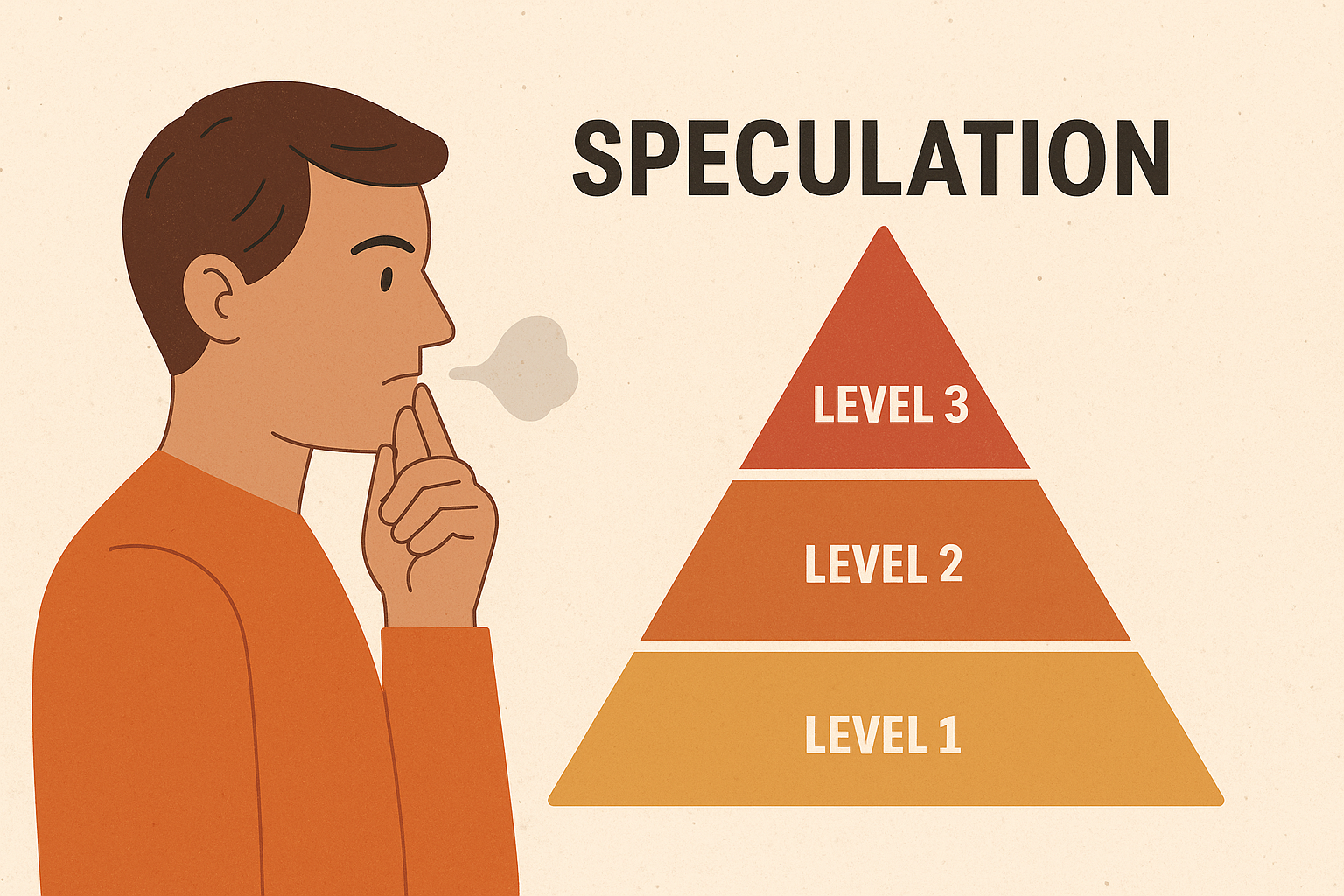

Recently, I developed a working model for speculation, categorizing it into levels: first, second, and third. It’s not an academic system per se, but as it turns out, it lines up beautifully with both ancient philosophy and modern cognitive science. Let’s take a walk through it.

First-Level Speculation: Reading the Physical

Imagine you’re watching a heated argument. One person finally exhales deeply as it ends. Without venturing into mystical mind-reading, you can infer something basic: that exhale likely relieved stress. This is first-level speculation — it’s grounded in observable biological realities.

The limbic system, the seat of emotional and stress responses in the brain, often triggers deep breathing after intense emotional experiences. This physiological pattern is well-documented (LeDoux, The Emotional Brain, 1998). Thus, connecting an exhale to stress relief isn’t wild guesswork; it’s a cautious, educated inference.

In classical philosophy, Aristotle called this kind of knowledge epistēmē: scientific understanding based on first principles (Posterior Analytics). It’s the closest we can get to certainty in the human world.

Second-Level Speculation: Assuming Feelings and Thoughts

Now, suppose you say, “That exhale means he’s guilty.” Here, you step beyond the body into the mind. This is second-level speculation: interpreting hidden emotional states based on external signs.

Psychologists have a name for the danger here: mind reading. David Burns, in The Feeling Good Handbook (1999), classifies it as a cognitive distortion. It’s plausible — but not verifiable without confirmation.

Aristotle would have called this doxa: opinion, not certain knowledge (Topics). Opinions can be wise or foolish, but they’re never fully trustworthy without further evidence.

Third-Level Speculation: Predicting the Future

The riskiest move comes when you push even further: “Because he exhaled and looked stressed, he’ll apologize tomorrow.”

This is third-level speculation: trying to foresee future actions based on shaky assumptions. Karl Popper, one of the most influential philosophers of science, warned heavily against this in The Logic of Scientific Discovery (2002). Future behavior is influenced by countless variables; unless your model is tested and falsifiable, it’s little more than a shot in the dark.

Plato, too, recognized this danger. In Republic Book VI, he discusses eikasia — the lowest form of knowledge, based on shadows and appearances rather than real understanding.

Why Structure Matters

Why does this distinction between levels matter? Because it disciplines the mind. It prevents us from sliding thoughtlessly from “what I see” to “what I feel” to “what I predict,” all without evidence.

Karl Popper outlined a solution: falsification. Every guess must be framed so it could be proven wrong. First-level speculations are usually testable. Second-level speculations are hard to test without direct communication. Third-level speculations often can’t be tested until after the event — and by then, you’re dealing in hindsight, not foresight.

In short: the more your speculation is anchored to observable facts and testable hypotheses, the more reliable it is.

An Analogy: Building a House on Solid Ground

Think of speculation like building a house.

- First Level: You build on bedrock. Your foundation (observation) is solid. Sure, it could crack if an earthquake comes, but day-to-day, it’s trustworthy.

- Second Level: You build on packed dirt. It’s decent but shifts with the seasons. You might stay upright for a while, but the risks of tilt and collapse are real.

- Third Level: You build on a swamp. It looks solid on top but step wrong, and you’ll sink. Predictions based on third-level speculation are like leaning your whole house on a patch of reeds.

The ancient philosophers would have smiled at this analogy. Popper might have drawn a blueprint.

How to Harness First-Level Speculation (Without Falling into the Trap)

- Mark your borders. Always ask: “Where does my observation end and my guess begin?” If you can’t clearly tell, back up.

- Phrase conditionally. Instead of declaring, “He is guilty,” say, “Given his body language, he may be feeling stress.” It leaves room for error and invites clarification.

- Test whenever possible. If you can verify your inference, do it. Otherwise, treat it as provisional.

- Know your limits. Recognize that second- and third-level speculations are inherently fragile. Use them sparingly and label them for what they are: possibilities, not certainties.

Why We Fall into Second- and Third-Level Speculation

It’s tempting. Humans are storytelling creatures. We don’t just observe — we interpret, narrate, and predict. Our brains crave patterns and closure. As Kahneman described in Thinking, Fast and Slow (2011), our “System 1” thinking leaps to conclusions quickly, favoring coherent stories over messy realities.

Exhaling after an argument becomes, in our minds, a Shakespearean drama of guilt, regret, and noble repentance — even if the person simply had gas.

Speculation in Everyday Life: A Double-Edged Sword

In law, medicine, and counseling, staying at first-level speculation can be the difference between a correct diagnosis and a tragic mistake. A doctor notes symptoms (observable facts), but to leap straight to a diagnosis without tests would be reckless.

In relationships, assuming someone’s feelings (second-level speculation) or predicting their future behavior (third-level speculation) often leads to misunderstanding, resentment, or broken trust.

Imagine assuming a friend who cancels dinner “must” be angry with you (second-level) and then predicting she’ll “probably ghost you forever” (third-level). How many friendships have been wrecked by spirals like that?

A Practical Framework for Healthy Speculation

When you observe something:

- First, describe only what you can see (“he exhaled deeply”).

- Then, infer cautiously from known patterns (“deep exhalation often signals stress relief”).

- Next, if tempted to speculate about feelings or future behavior, stop and label it: “This is second- or third-level speculation.”

- Finally, seek confirmation before treating your speculation as fact.

This mental discipline will keep you grounded, compassionate, and wise.

Final Thoughts

Speculation is like a tool. In the right hands, it’s a compass guiding you through the fog of human complexity. In the wrong hands, it’s a wrecking ball, smashing relationships, theories, and reputations.

Ancient thinkers like Aristotle and Plato, and modern minds like Karl Popper, left us a treasure map. The further you go from observation to assumption to prediction, the shakier the ground beneath you becomes.

Use speculation — but build on bedrock, not on sand.

Sources Cited:

- Aristotle. Posterior Analytics. Oxford University Press, 1993.

- Aristotle. Topics. Oxford University Press, 1997.

- Burns, David D. The Feeling Good Handbook. Plume, 1999.

- Kahneman, Daniel. Thinking, Fast and Slow. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2011.

- LeDoux, Joseph. The Emotional Brain. Simon and Schuster, 1998.

- Plato. Republic, Book VI. Hackett Publishing, 1992.

- Popper, Karl. Conjectures and Refutations: The Growth of Scientific Knowledge. Routledge, 1963.

- Popper, Karl. The Logic of Scientific Discovery. Routledge, 2002.